LurkerSix

OG

Post was too big so heres pt.2

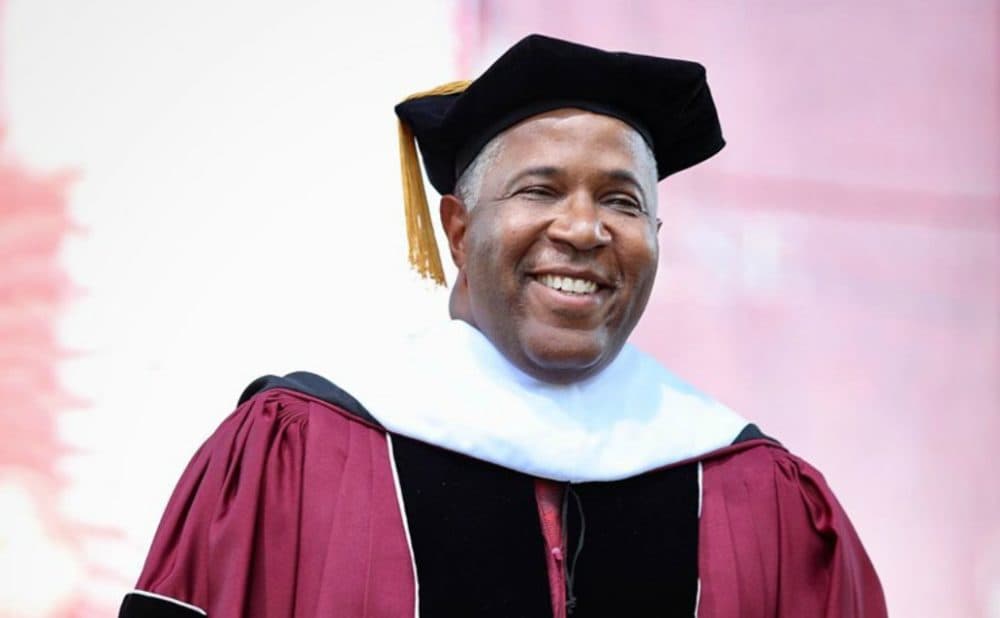

But the my main post is this, he didnt start caring about black people or charities till after he got caught for tax evasion.

But the my main post is this, he didnt start caring about black people or charities till after he got caught for tax evasion.

Eventually, however, the risks of his old deal with Brockman became manifest: Sometime between November 2013 and January 2014, Smith received a clue that U.S. tax officials were scrutinizing his accounts.

During that period, officials at a Swiss bank advised Smith the bank was going to participate in a U.S. Justice Department program for the disclosure of Americans’ overseas accounts, according to Smith’s statement. The bank requested that Smith waive the secrecy of his account and recommended he apply to a voluntary IRS program to disclose foreign money.

Smith applied for the IRS program in March 2014 but was quickly rejected. This is typically a sign the agency already is scrutinizing the applicant’s tax filings, former federal prosecutors said.

When a person’s application to the program is rejected in this manner, “the IRS is basically telling you ... that the IRS knows something about you or is looking at your returns already,” said George Abney, a former prosecutor in the Justice Department’s tax division who is now in private practice. “It could be something small, or it could be something large, as it appears to have been in this case.”

The standard legal advice, in such situations, Abney said, “is to go ahead and fix everything. That way if the IRS does come knocking, you can tell them we’ve already corrected the problem and that will put you in a better light.”

It is about this time that Smith became a major philanthropist, frequently making headlines with his generosity.

He’d previously used $13 million in untaxed funds to make improvements to a residence in Colorado and fund “charitable activities at the property,” the Justice Department said in a news release announcing its deal with Smith. That property appears to be Lincoln Hills, established in the 1920s to offer Black people a mountain getaway in the era of segregation. Smith converted it into a vacation home for his family and used it to host former foster children and trafficking victims. He also co-founded a nonprofit, Lincoln Hills Cares, that provides outdoor opportunities for Colorado’s underprivileged youth.

His big foray into philanthropy started in 2014, when he established the Fund II Foundation, and filled its coffers with over $182 million in assets from the offshore accounts where he had hidden his income, according to the Justice Department and the foundation’s tax filings.

Why Smith initiated so much charity at this point is unclear. But over the same period, Smith’s personal life and his business were undergoing major upheavals.

The same month, Smith and his partners sold a minority stake in Vista Equity Partners to another private equity firm, a move that probably would have enriched him, better enabling him to become a donor.

The charity moves also might have been strategic, too, some tax experts said. If the money in the offshore entities was going to good causes, the tax evasion might strike prosecutors and juries as less wrongful.

The large donation to his foundation came from a Belize-based trust called Excelsior, which Smith controlled, and consisted of shares in a second offshore entity, a Nevis-based shell company called Flash, according to the foundation’s tax filings and statements by the Justice Department. These were the same entities Smith had established in 2000 in his agreement with Brockman, according to Smith’s statement. As part of his agreement with the federal government, Smith admits that he used those entities to hide over $200 million in income.

The foundation states on its website that the money in those entities was always meant to go toward charity. The foundation was formed pursuant to an agreement between Smith’s private equity firm, Vista Equity Partners, and the Bermuda-based company that Brockman had created to invest in the Vista fund. The foundation says the parties agreed that when the fund wound down, any leftover assets would be given to charity.

But according to the statement Smith signed with prosecutors, Smith “knowingly and intentionally falsely claimed that this charitable contribution was required as part of an agreement” with Brockman

Regardless of these charitable donations from the offshore entities, however, some attorneys said, Smith is fortunate to have avoided criminal prosecution, especially given the scale of the tax evasion.

“The idea of a billionaire tax cheat getting immunity to cooperate against another billionaire tax cheat strikes a lot of people as out of step,” said Justin Weddle, a former federal prosecutor who handled several large tax cases and is now in private practice. “For Smith to get a non-prosecution agreement for cooperation is very unusual.”.

Under his deal with federal prosecutors, Smith abandons claims for a $182 million tax refund, which consisted partly of claims for charitable deductions that he made in 2018 and 2019, the Justice Department said.

Weddle noted, too, that the tax evasion scheme strikes him as a particularly ill-advised strategy for both Brockman and Smith, because while it might have saved them tens of millions of dollars, those amounts are small compared to their huge fortunes.

“It strikes me as dumb,” Weddle said. Smith “was risking criminal prosecution for a tiny portion of his portfolio.”

To review his tax situation, Smith had earlier hired tax attorneys including Charles Rettig, whom President Trump appointed as IRS commissioner in 2018, according to two people familiar with the hiring but who were not permitted to speak publicly. It is unknown what advice Rettig or the other tax experts gave Smith.

“The Commissioner did not have any role in the DoJ investigation into Robert Smith,” the IRS said in statement. “Without acknowledging whether the Commissioner represented any particular client in any particular matter while he was in private practice, the Commissioner recused himself from all such matters upon taking office.”

Tax experts said wealthy people such as Smith can reap significant financial benefits from their charitable gifts and can enhance their public reputations.

“It’s certainly a very troubling case in terms of shining a light on the extent to which wealthy Americans are avoiding taxes through offshore vehicles,” said Ray Madoff, a professor at Boston College and an expert on philanthropy and taxation. "On the charitable side, it raises questions about people’s ability to offset significant taxable income with charitable donations.”