LurkerSix

OG

Nvidia Wants to Replace Nurses With AI for $9 an Hour

Your health could soon be in the hands of Nvidia-powered AI nurses, and they cost your healthcare provider next to nothing.

gizmodo.com

gizmodo.com

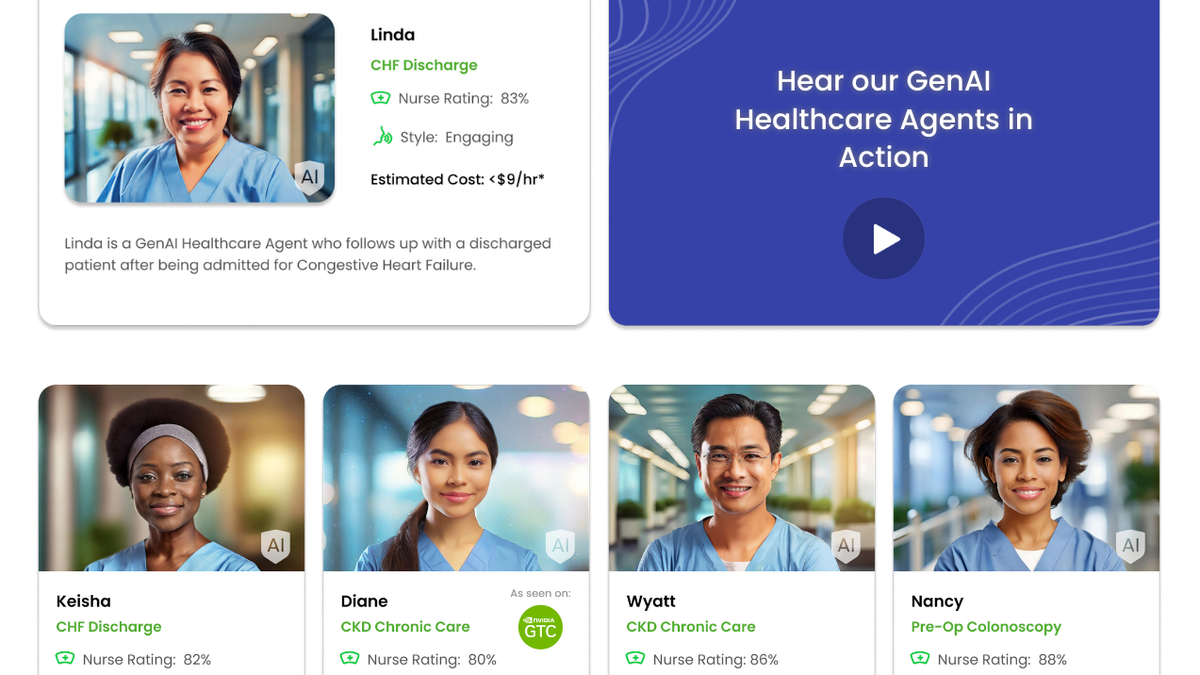

Nvidia announced a collaboration with Hippocratic AI on Monday, a healthcare company that offers generative AI nurses who work for just $9 an hour. Hippocratic promotes how it can undercut real human nurses, who can cost $90 an hour, with its cheap AI agents that offer medical advice to patients over video calls in real-time.

“Voice-based digital agents powered by generative AI can usher in an age of abundance in healthcare, but only if the technology responds to patients as a human would,” said Kimberly Powell, vice president of Healthcare at NVIDIA in a press release Monday.

Nvidia is powering Hippocratic’s real-time responses over video calls. In a demo posted by Nvidia, a semi-human-looking AI agent named Rachel verbally instructs a patient on how to take penicillin. The agent then tells the patient it will report back all this information to her real human doctor. Rachel is one of many AI nurses that healthcare providers can choose from, according to one of Hippocratic’s product pages. The AI nurses range in specialties from “Colonoscopy Screening” to “Breast Cancer Care Manager,” all for less than minimum wage.

Hippocratic directly promotes how it can undercut the living wages of real nurses as a feature, not a bug. One page of the company’s website compares a human nurse’s $90 per hour salary to an AI agent’s $9 an-hour running costs. Hippocratic claims its AI nurses outperform human nurses regarding bedside manner, education, and narrowly miss on satisfaction, according to a survey.

The introduction of AI healthcare agents comes at a tumultuous time for the nursing industry. Over 32,000 nurses went on strikes around the country in 2023, representing a quarter of all major strikes in the United States, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Nurses are dealing with worker shortages, that predate the covid-19 pandemic, which Hippocratic seeks to address.

The Hippocratic collaboration was one of many announcements from Nvidia’s 2024 GTC Conference, but this AI development was perhaps the most dystopian. Hippocratic says its AI nurses were tested by thousands of human nurses and hundreds of human doctors. The company’s technology is being tested by over 40 healthcare providers around the country.

“With Generative AI, the incremental cost of healthcare access and interventions is trending to zero,” says Hippocratic on its About page. “LLMs are the only scalable way to close this gap,” referring to the difference in healthcare supply and demand.

The AI company working with Nvidia says its generative AI nurses are not sufficient to make diagnoses. The AI healthcare agent is trained to engage a human when appropriate. Hippocratic’s name is inspired by The Hippocratic Oath, a code of ethics that physicians adhere to that means to “first, do no harm.”