DOS_patos

Unverified Legion of Trill member

“Maybe the law ain’t perfect, but it’s the only one we got, and without it we got nuthin” – Bass Reeves

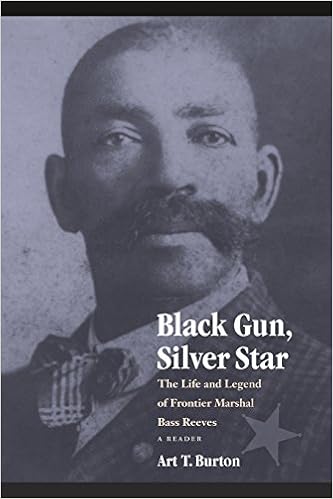

Born to slave parents in 1838 in Crawford County, Arkansas, Bass Reeves would become the first black U.S. Deputy Marshal west of the Mississippi River and one of the greatest frontier heroes in our nation’s history.

Owned by a man named William Reeves, a farmer and politician, Bass took the surname of his owner, like other slaves of the time. His first name came from his grandfather, Basse Washington

Working alongside his parents, Reeves started out as a water boy until he was old enough to become a field hand. In about 1846, William Reeves moved his operations, family, and slaves to Grayson County, Texas.

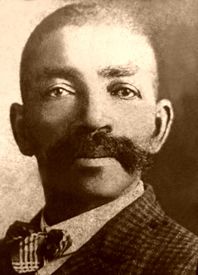

Bass was a tall young man, at 6’2”, with good manners and a sense of humor. George Reeves, William’s son, later made him his valet, bodyguard, and personal companion. When the Civil War broke out, Texas sided with the Confederacy and George Reeves went into battle, taking Bass with him.

It was during these years of the Civil War that Bass parted company from Reeves, some say because Bass beat up George after a dispute in a card game. Others believe that Bass heard too much about the “freeing of slaves” and simply ran away. In any event, Bass fled to Indian Territory where he took refuge with the Seminole, Cherokee, and Creek Indians, learning their customs, languages, and tracking skills. Here, he also honed his firearm skills, becoming very quick and accurate with a pistol. Though Reeves claimed to be “only fair” with a rifle, he was barred on a regular basis from competitive turkey shoots.

“Freed” by the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 and no longer a fugitive, Reeves left Indian Territory and bought land near Van Buren, Arkansas, where he became a successful farmer and rancher. A year later, he married Nellie Jennie from Texas, and immediately began to have a family. Raising 10 children on their homestead — five girls and five boys, the family lived happily on the farm. During this time, oral history states that Reeves sometimes served as a scout and guide for U.S. Deputy Marshals going into Indian Territory on business for the Van Buren Federal Court, which had jurisdiction over Indian Territory.

Reeve’s life as a contented farmer would change when the Federal Western District Court was moved to Fort Smith, Arkansas and Isaac C. Parker was appointed on May 10, 1875. At that time, Indian Territory had become extremely lawless as thieves, murderers, and anyone else wishing to hide from the law, took refuge in the territory that previously had no federal or state jurisdiction.

One of Parker’s first official acts was to appoint U.S. Marshal James F. Fagan as head of the some 200 deputies he was then told to hire. Fagan heard of Bass Reeves’ significant knowledge of the area, as well as his ability to speak several tribal languages, and soon recruited him as a U.S. Deputy.

The deputies were tasked with “cleaning up” Indian Territory and on Judge Parker’s orders, “Bring them in alive — or dead!”

Working among other lawmen that would also become legendary, such as Heck Thomas, Bud Ledbetter, andBill Tilghman, Reeves began to ride the Oklahoma range in search of outlaws. Covering some 75,000 square miles, the United States Court at Fort Smith, was the largest in the nation.

Depending on the outlaws for whom he was searching, a deputy would generally take with him from Fort Smith, a wagon, a cook, and a Native American posseman. Often they rode to such places as Fort Reno, Fort Sill and Anadarko, a round trip of more than 800 miles.

Though Reeves could not read or write it did not curb his effectiveness in bringing back the criminals. Before he headed out, he would have someone read him the warrants and memorize the contents and which warrant was which. When asked to produce the warrant, he never failed to pick out the correct one.

An imposing figure, always riding on a large white stallion, Reeves began to earn a reputation for his courage and success at bringing in or killing many desperadoes of the territory. Always wearing a large hat, Reeves was usually a spiffy dresser, with his boots polished to a gleaming shine. He was known for his politeness and courteous manner. However, when the purpose served him, he was a master of disguises and often utilized aliases.

Sometimes appearing as a cowboy, farmer, gunslinger, or outlaw, himself, he always wore two Colt pistols, butt forward for a fast draw. Ambidextrous, he rarely missed his mark.

Leaving Fort Smith, often with a pocketful of warrants, Reeves would return months later herding a number of outlaws charged with crimes ranging from bootlegging to murder. Paid in fees and rewards, he would make a handsome profit, before spending a little time with his family, and returning to the range once again.

The tales of his captures are legendary – filled with intrigue, imagination, and courage. On one such occasion, Reeves was pursuing two outlaws in the Red River Valley near the Texas border. Gathering a posse, Reeves and the other men set up camp some 28 miles from where the two were thought to be hiding at their mother’s home. After studying the terrain and making a plan, he soon disguised himself as a tramp, hiding the tools of his trade – handcuffs, pistol, and badge, under his clothes. Setting out on foot, he arrived at the house wearing an old pair of shoes, dirty clothes, carrying a cane, and wearing a floppy hat complete with three bullet holes.

Upon arriving at the home, he told a tale to the woman who answered the door, that his feet were aching after having been pursued by a posse who had put the three bullet holes in his hat. After asking for a bite to eat, she invited him in and while he was eating she began to tell him of her two young outlaw sons, suggesting that the three of them should join forces.

Feigning weariness, she consented to let him stay a while longer. As the sun was setting, Reeves heard a sharp whistle coming from beyond the house. Shortly afterward, the woman went outside and responded with an answering whistle. Before long, two riders rode up to the house, talking at length with her outside. The three of them then came inside and she introduced her sons to Reeves. After discussing their various crimes, the trio agreed that it would be a good idea to join up.

Bunking down in the same room, Reeves watched the pair carefully as they drifted off to sleep and when they were snoring deeply, handcuffed the pair without waking them. When early morning approached, he kicked the boys awake and marched them out the door. Followed for the first three miles by their mother, who cursed Reeves the entire time, he marched the pair the full 28 miles to the camp where the posse men waited. Within days, the outlaws were delivered to the authorities and Bass collected a $5,000 reward.

Born to slave parents in 1838 in Crawford County, Arkansas, Bass Reeves would become the first black U.S. Deputy Marshal west of the Mississippi River and one of the greatest frontier heroes in our nation’s history.

Owned by a man named William Reeves, a farmer and politician, Bass took the surname of his owner, like other slaves of the time. His first name came from his grandfather, Basse Washington

Working alongside his parents, Reeves started out as a water boy until he was old enough to become a field hand. In about 1846, William Reeves moved his operations, family, and slaves to Grayson County, Texas.

Bass was a tall young man, at 6’2”, with good manners and a sense of humor. George Reeves, William’s son, later made him his valet, bodyguard, and personal companion. When the Civil War broke out, Texas sided with the Confederacy and George Reeves went into battle, taking Bass with him.

It was during these years of the Civil War that Bass parted company from Reeves, some say because Bass beat up George after a dispute in a card game. Others believe that Bass heard too much about the “freeing of slaves” and simply ran away. In any event, Bass fled to Indian Territory where he took refuge with the Seminole, Cherokee, and Creek Indians, learning their customs, languages, and tracking skills. Here, he also honed his firearm skills, becoming very quick and accurate with a pistol. Though Reeves claimed to be “only fair” with a rifle, he was barred on a regular basis from competitive turkey shoots.

“Freed” by the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 and no longer a fugitive, Reeves left Indian Territory and bought land near Van Buren, Arkansas, where he became a successful farmer and rancher. A year later, he married Nellie Jennie from Texas, and immediately began to have a family. Raising 10 children on their homestead — five girls and five boys, the family lived happily on the farm. During this time, oral history states that Reeves sometimes served as a scout and guide for U.S. Deputy Marshals going into Indian Territory on business for the Van Buren Federal Court, which had jurisdiction over Indian Territory.

Reeve’s life as a contented farmer would change when the Federal Western District Court was moved to Fort Smith, Arkansas and Isaac C. Parker was appointed on May 10, 1875. At that time, Indian Territory had become extremely lawless as thieves, murderers, and anyone else wishing to hide from the law, took refuge in the territory that previously had no federal or state jurisdiction.

One of Parker’s first official acts was to appoint U.S. Marshal James F. Fagan as head of the some 200 deputies he was then told to hire. Fagan heard of Bass Reeves’ significant knowledge of the area, as well as his ability to speak several tribal languages, and soon recruited him as a U.S. Deputy.

The deputies were tasked with “cleaning up” Indian Territory and on Judge Parker’s orders, “Bring them in alive — or dead!”

Working among other lawmen that would also become legendary, such as Heck Thomas, Bud Ledbetter, andBill Tilghman, Reeves began to ride the Oklahoma range in search of outlaws. Covering some 75,000 square miles, the United States Court at Fort Smith, was the largest in the nation.

Depending on the outlaws for whom he was searching, a deputy would generally take with him from Fort Smith, a wagon, a cook, and a Native American posseman. Often they rode to such places as Fort Reno, Fort Sill and Anadarko, a round trip of more than 800 miles.

Though Reeves could not read or write it did not curb his effectiveness in bringing back the criminals. Before he headed out, he would have someone read him the warrants and memorize the contents and which warrant was which. When asked to produce the warrant, he never failed to pick out the correct one.

An imposing figure, always riding on a large white stallion, Reeves began to earn a reputation for his courage and success at bringing in or killing many desperadoes of the territory. Always wearing a large hat, Reeves was usually a spiffy dresser, with his boots polished to a gleaming shine. He was known for his politeness and courteous manner. However, when the purpose served him, he was a master of disguises and often utilized aliases.

Sometimes appearing as a cowboy, farmer, gunslinger, or outlaw, himself, he always wore two Colt pistols, butt forward for a fast draw. Ambidextrous, he rarely missed his mark.

Leaving Fort Smith, often with a pocketful of warrants, Reeves would return months later herding a number of outlaws charged with crimes ranging from bootlegging to murder. Paid in fees and rewards, he would make a handsome profit, before spending a little time with his family, and returning to the range once again.

The tales of his captures are legendary – filled with intrigue, imagination, and courage. On one such occasion, Reeves was pursuing two outlaws in the Red River Valley near the Texas border. Gathering a posse, Reeves and the other men set up camp some 28 miles from where the two were thought to be hiding at their mother’s home. After studying the terrain and making a plan, he soon disguised himself as a tramp, hiding the tools of his trade – handcuffs, pistol, and badge, under his clothes. Setting out on foot, he arrived at the house wearing an old pair of shoes, dirty clothes, carrying a cane, and wearing a floppy hat complete with three bullet holes.

Upon arriving at the home, he told a tale to the woman who answered the door, that his feet were aching after having been pursued by a posse who had put the three bullet holes in his hat. After asking for a bite to eat, she invited him in and while he was eating she began to tell him of her two young outlaw sons, suggesting that the three of them should join forces.

Feigning weariness, she consented to let him stay a while longer. As the sun was setting, Reeves heard a sharp whistle coming from beyond the house. Shortly afterward, the woman went outside and responded with an answering whistle. Before long, two riders rode up to the house, talking at length with her outside. The three of them then came inside and she introduced her sons to Reeves. After discussing their various crimes, the trio agreed that it would be a good idea to join up.

Bunking down in the same room, Reeves watched the pair carefully as they drifted off to sleep and when they were snoring deeply, handcuffed the pair without waking them. When early morning approached, he kicked the boys awake and marched them out the door. Followed for the first three miles by their mother, who cursed Reeves the entire time, he marched the pair the full 28 miles to the camp where the posse men waited. Within days, the outlaws were delivered to the authorities and Bass collected a $5,000 reward.