Minneapolis police discover 1,700 untested rape kits spanning 30 years

Some date to 1990s; the number far surpasses the 194 reported in a 2015 audit.

An internal review of sexual assault cases in Minneapolis turned up an estimated 1,700 untested rape kits from as far back as the 1990s — a backlog that officials say could take at least two years to clear.

The startling revelation was announced at a City Hall news conference Friday, during which department officials announced plans to hire three additional analysts to help process the forensic evidence kits.

The latest count far surpasses the 194 untested kits reported during an 2015 audit, part of what Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey called an “unjustified mistake” that left years of potential evidence sitting in police storage.

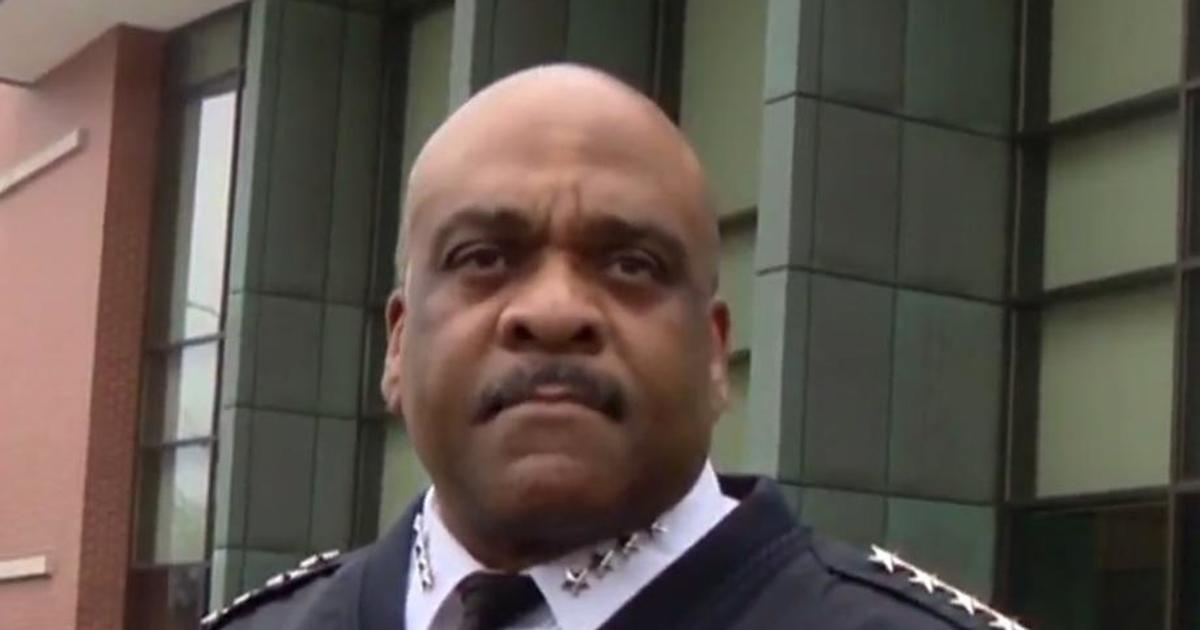

Speaking to reporters, Police Chief Medaria Arradondo said he had no explanation for the discrepancy in the reported numbers or why so many kits went untested, but he vowed to eliminate the backlog by working with department agencies and advocates to ensure that the kits are tested and victims are notified compassionately.

The department’s sex crimes unit is still conducting a final count to determine how many kits remain, which comes amid a national reckoning over sexual harassment and assault.

“We have a failure in terms of auditing and processing that is unacceptable,” Arradondo said. “I very honestly stand before you to say we still don’t know why that [miscount] did occur back in 2015, but moving forward I can ensure you that it will never happen again.”

He said that for the department to rebuild trust it needed to own up to its past mistakes.

Mike Sauro, a retired lieutenant who ran the sex crimes unit in 2015, defended his handling of the kits, saying a similar audit completed years ago showed far fewer. Most of the kits were deemed “restricted,” meaning the victim wasn’t involved in the investigation, and thus they were never sent to the state forensic lab for testing and matching against a national database of offender DNA.

“We reviewed all the kits from the year 2000 all the way up to 2015,” he said in a phone interview Friday. “People have this misconception that all kits have to be and should be tested, and that’s just not true. … If you don’t have an official police report made, we can’t enter them into the national database, so we can’t test them.”

Kenosha Davenport, executive director of the Sexual Violence Center, said the group will work with police and form a committee to grapple with the moral and ethical considerations that arise from reopening old cases, while avoiding retraumatizing victims.

“When you look at the span of someone’s lifetime you know the healing journey isn’t a linear journey, so we have victims who may not have shared with their partner or children,” she said. “It’s critical that the notification process is done diligently and with the support of advocates so we can continue to support them.”

Prosecutors will have to examine each case to determine whether any statute of limitations applies, said Chuck Laszewski, a spokesman for the Hennepin County Attorney’s Office. Even then, he said, securing a conviction in rape cases can be challenging.

“It has always been and it continues to be a difficult crime to get a guilty verdict,” he said. “There’s usually only two people, there’s usually not witnesses, so it can be difficult to provide enough evidence to get a jury to prove them guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.”

Deputy chief Erick Fors said the untested kits were discovered in July, when the department was accounting for untested kits that need to be sent to the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension (BCA) under state law. The kits, he said, are inventoried, sorted and maintained in police storage facilities around the city, and they’re now being physically tallied to determine a final number.

All have been properly stored, he said. The department is now working with the BCA to fund additional analysts to process the untested kits, and more than 60 untested kits have already been sent to the agency, he said. “The culture has changed, and we have an obligation to test these kits,” Fors said. “We’re looking at some periods of time where that philosophy wasn’t applied, and we really see the benefit to have this done. Hopefully this will not only result in people getting justice, but this is a debt that we owe.”

The revelation of the untested kits comes one year after the Star Tribune series “

Denied Justice” documented widespread failings in the investigation and prosecution of sexual assault in Minnesota and spurred changes by police departments and county prosecutors throughout the state. Minnesota police frequently struggled to investigate cases of sex assault in the years reviewed, often failing to interview witnesses, collect evidence or even assign detectives in cases in which the victim was drinking, the monthslong investigation found.

Only about one in four sex-assault reports filed with Minneapolis police is sent to the county attorney for prosecution.

The department recently has joined other law enforcement agencies around the state in taking steps to identify and process every untested kit. The department hired a victims advocate last August to work alongside investigators and help rape survivors navigate the sometimes labyrinthine process of reporting an assault.

Friday’s announcement was met with frustration and condemnation in victim-advocacy circles.

Jude Foster, of the state Coalition Against Sexual Assault, said she was shocked but not surprised by the staggering number of untested kits. But she also saw it as sign that law enforcement is starting to take such cases seriously. She likened it to Detroit, where officials pushed hard to clear a backlog of more than 11,000 untested kits, subsequent testing of which identified hundreds of potential suspects.

“I felt really encouraged that the mayor of Minneapolis is taking this seriously, that the chief of police is taking this seriously. … I saw transparency and accountability today,” said Foster, the agency’s statewide medical forensic policy program coordinator. “That means that law enforcement is really looking at past practices, and that means that things are really starting to change.”

Law enforcement agencies in Duluth and Anoka County have received federal grants to help speed their efforts to process untested rape kits and reopen cases, she said.

In a joint statement, state Reps. Jamie Becker-Finn and Kelly Moller called the city’s backlog unacceptable and pledged to work with the BCA and advocates to ensure the kits are tested “as soon as possible and survivors are notified.”

“These kits represent hundreds of survivors who sought justice and have gone years or even decades without receiving it,” the statement read.

Under the state’s rape law enacted last year, police have 10 days to retrieve unrestricted exam kits from health care facilities and 60 days to submit them for testing. They are also required, when asked, to inform victims about the status of their kits and any findings. Police are not required to test every kit connected to a reported crime, including in cases in which they think the results hold no evidentiary value, although they must explain why in writing.